[As I mentioned in the previous post, I wrote a paper about IF for a graduate class in literary theory, circa 1994. I think it’s the first thing I ever wrote about interactive fiction — before I knew anything about the indie IF scene or the int-fiction newsgroups at all. Below is that paper, HTML-ized and with various links added, but otherwise identical to what I turned in.]

>examine the map

The map shows a network of boxes connected by lines and arrows, with many erasures and scrawled additions. Something about the pattern is maddeningly familiar; but you still can’t put your finger on where you’ve seen it before.

>examine the book

The open book is so wide, it’s impossible to touch both edges with your arms outstretched. Its thousands of vellum leaves form a two-foot heap on either side of the spine; the rich binding probably required the cooperation of twenty calves.

The magpie croaks, “Then stand back! ‘Cause it go BOOM. Awk!”

>read the book

It’s hard to divine the purpose of the calligraphy. Every page begins with a descriptive heading (“Wabewalker’s encounter with a Magpie,” for instance) followed by a list of imperatives (prayers? formulae?), each preceded by an arrow-shaped glyph.

The writing ends abruptly on the page you found open, under the heading “Wabewalker puzzles yet again over the Book of Hours.” The last few incantations read:

>EXAMINE THE MAP

>EXAMINE THE BOOK

>READ THE BOOK

—Trinity with Paul O’Brian

An electronic fiction is not only a fictional universe but a universe of possible fictions.

–Jay David Bolter (Tuman 34)

The long passage above is from a fictional text about an adventurous individual who discovers the secrets of a magical land in order to avert nuclear annihilation on Earth. It has all the qualities of a traditional1 fantasy narrative — fantastic setting, magical transportation, eerie symbolism — but it is not a traditional fantasy narrative. It has no pages, no hard covers, in fact it isn’t a book at all. It is a piece of computer software, an adventure game entitled Trinity, one which boasts no graphics or fancy features — just text and a “parser” programmed to understand simple sentences typed by the player. Its makers, a company called Infocom, call it “interactive fiction,” and the sentences following the “>” sign were typed by me, accepted into the computer, and processed for a response. The scene I chose was a rather metafictional one, where the player/reader comes across a book within the context of the game which records every move that he or she types at the prompt (“>”).

Interactive fiction (hereafter shortened to IF) is an extremely new form, the most primitive incarnation of which surfaced only about 20 years ago, but already it challenges deeply entrenched notions of narrative, authorship, and reading theory. It demands (and helps to enact) new theories of subjectivity, and presents us with a narrative form which is familiar in some ways, but which in other ways is utterly alien. Its novelty and its radical differences from print narrative make it difficult to theorize, but I hope to make a few definite steps in that direction here. As I see it, literary criticism of traditional texts, especially reader-response criticism, can help us in an endeavor to understand this new form. Theorists like Wolfgang Iser, Norman Holland, and Stanley Fish have created theories aimed at traditional texts which seem custom-made for interactive fiction. In this paper, I will attempt to theorize the computer text through the lens of their theories, and to explore the avenues opened by interactive fiction which offer both a better understanding of this tremendously potent literary form and a fresh perspective on literary theory itself. Before this is possible, however, we need a clearer understanding of the subject at hand.

WHAT IS IF?

Previous critical approaches to IF have had to concern themselves so much with explaining how it came to exist that by the time they got to theorizing, they had largely run out of steam. I hope to avoid that trap by providing an extremely brief history of the evolution of IF, and referring the curious reader to Anthony Niesz and Norman Holland, who provide the best concise narrative of IF’s development.

IF developed in the early 1970s on large university mainframe computers, at which point it was little different from the Choose-Your-Own-Adventure novels of print fiction (“If you want to get in the helicopter, turn to page 12. If you want to go home, turn to page 16”). David Lebling and Marc Blank, working on the mainframe at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, co-authored Zork, the first game whose parser could understand complete sentences (“Get all but the dagger and the rope”) rather than simple two word commands (“look frog”). The game, a sword-and-sorcery treasure hunt in the Dungeons and Dragons pattern, spread rapidly to other mainframe systems and was such a tremendous success that when personal computers began to proliferate, Blank and Lebling transposed Zork to the PC format and founded a company, Infocom, from which to sell it. Again, it was successful, and Infocom followed it with four sequels (a fifth is forthcoming) and more than 25 other works of IF in the literary traditions of mystery, science-fiction, adventure, romance, and others. Many other companies created programs which followed this trend, but Infocom remained the publisher not only of the highest quality software, but that most dedicated to textual IF rather than graphics or sound-augmented games; for the purpose of clarity and simplicity, this paper will deal only with Infocom programs.2

As indicated by the passage quoted from Trinity, the text of interactive fiction comes in rather short blocks, interrupted by prompts. At a prompt, the program will wait for the player to input her next move. The narrative will not continue until the player responds. Input can consist of anything from the briefest commands (“yell”) to fairly complex sentences (for example, an instruction manual lists “TAKE THE BOOK THEN READ ABOUT THE JESTER IN THE BOOK” as a possible command). The program addresses the player in the second person singular (“you still can’t put your finger on where you’ve seen it before”), a mode which raises interesting questions about the reader’s subjectivity.

IF also calls into question the basic notion of narrative linearity. An Infocom advertising pamphlet reads:

you can actually shape the story’s course of events through your choice of actions. And you have hundreds of alternatives at every step. In fact, an Infocom interactive story is roughly the length of a short novel in content, but there’s so much you can see and do, your adventure can last for weeks, even months. (Incomplete Works)

If the shape of a traditional narrative is a line, an interactive narrative is better conceived of as a web.3 Each prompt, each location in the story, is a nexus from which hundreds of alternate pathways radiate, each leading to new loci. This is not to say that IF destroys linearity, but rather that it removes the responsibility for creating linearity from the author and hands it over directly to the reader. Readers of an IF create their own line through the text, a line which can be different at every reading.

IF AND TRADITIONAL TEXTS

Though it is highly divergent, IF is not completely divorced from traditional texts. For one thing, most IF themes, settings, and structures are drawn directly from literary traditions established by traditional print authors. This extraction can range from simple genre duplication, as in the generalized science-fiction feel of Starcross, to the direct appropriation of character and setting, as in Sherlock: Riddle of the Crown Jewels, a mystery based in Arthur Conan Doyle’s London.

Moreover, the programs often incorporate traditional texts into their packaging, texts which frequently contain clues to the puzzles contained within the game. Trinity, for example, includes a comic book dealing with the themes of the text. A Mind Forever Voyaging, which Infocom calls its “entry into the realm of serious science fiction such as 1984” (Unfold), contains an initial chapter in print which sets the scene for the computer narrative and introduces the player to his “role” within the game.

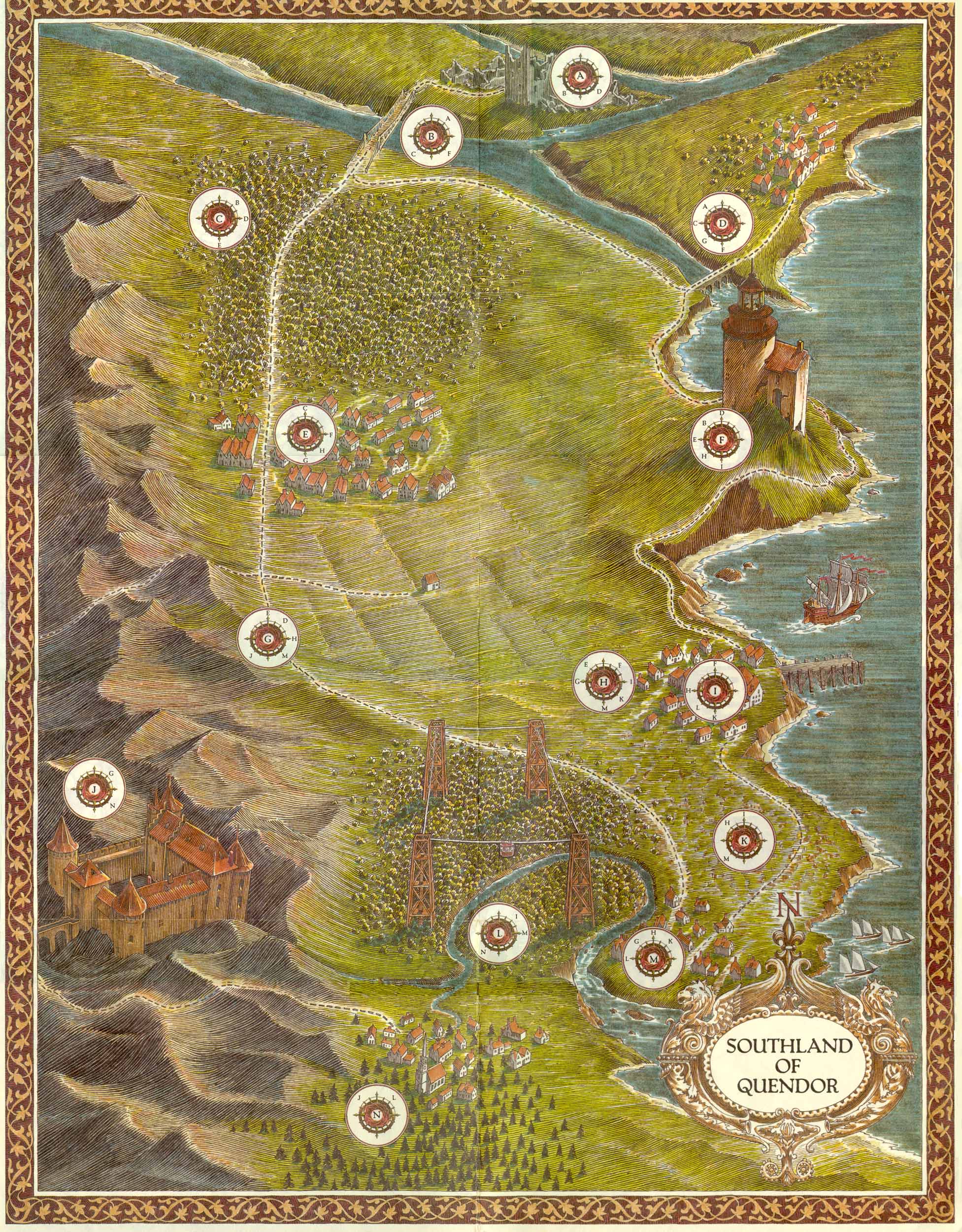

The line between interactive fiction and traditional print texts becomes further blurred when the player uses the SCRIPT function. SCRIPT commands the computer to print out a transcript of the game as it is being played, so that players can have a hard copy of the text they produce in collaboration with the game. Because of its radically different configuration, IF disrupts many of the characteristics often taken for granted in print fiction. For example, as Niesz and Holland point out, “Because the fiction is inseparable from the system that enables someone to read it, one cannot, as it were, hold the whole novel in one’s hand… One cannot look back at what went before” (120). One way to address these differences is through the SCRIPT function. Indeed, a game like Infidel, which includes a complex system of “hieroglyphics” for the reader to decipher, almost demands some type of transcription if the player is to be able to put the pieces of the code together. Furthermore, most players of IF make maps on paper in order to keep track of the complex web of locations the story. Though IF is essentially a computer-bound form, its readers often find themselves taking pen (or printer) to paper in order to resist the evanescence of screen scrolling.

However, IF’s removal from traditional texts is also one of its greatest advantages. In fact, I would argue that without computer technology, creating interactive fiction would be extremely difficult if not impossible. Choose-Your-Own-Adventure novels not only demand an arduous amount of page-flipping, the options they provide are only of the multiple-choice variety, as opposed to the much greater vocabulary-oriented option locus of IF. As Stuart Moulthrop and Nancy Kaplan argue, “the more intricate page-turning a text demands, the more conscious its reader is likely to become of the native sequence that he is being made to violate” (12). The computer’s advanced ability to handle high-speed calculations allows the text to become more truly interactive without any of the alienation produced by the print text which violates its own conventions. This makes the computer a necessary tool for IF; it is the only medium which allows the type of interactivity at issue here.

Finally, it is important to remember that although IF differs radically and in many ways from traditional texts, it is still a text. Its sentences and paragraphs may be interspersed with and guided by player input, but those sentences (as well as the sentences typed by the player) are still units of language susceptible to theories designed to analyze all such units. Literary theory is not obviated by the interactive text; rather it is pushed into new arenas.

THE NARRATIVE CURTAIN

Neil Randall’s analysis of IF includes a lucid explanation of one of its most noteworthy features: “interactive fiction disrupts the concept of the novel’s ‘last page’… an interactive fiction work’s only indication of ending… is the story’s announcement that the quest has been solved” (189). This effect is part of what I call the narrative curtain. IF allows its reader a certain initial area to explore, but draws a metaphorical curtain around its boundaries, a curtain which promises further expansion at the same time as it blocks the way. The reader’s task is to find the tools necessary to draw back the curtain and continue her progress through the narrative.

This curtain also operates at the level of player input. A player encountering an IF text for the first time has no idea of the limits of the program’s vocabulary, and must discover these limits by trial and error. Even after lengthy interaction, the player is always unable to construct a definitive list of words the parser understands — there always remains the possibility that the program understands words that the player hasn’t attempted. Thus, the curtain remains, promising expansion but blocking the reader’s vision of that expansion. This curtain is again made possible by the computer’s ability to hide parts of the text from the reader, a capability which print simply does not have, unless the narrative is serialized and forcibly withheld from its reader. It is this curtain which allows Niesz and Holland to conclude that “writing and reading as processes replace writing and reading as products” in IF (127).

“In general, the structure [of IF texts] is the Quest” (115), assert Niesz and Holland, and I would argue that this structure has been dictated by the power of the narrative curtain. Without a quest for the player to complete, the narrative curtain becomes more frustrating than satisfying. If the curtain is a puzzle to be solved, then passing through it is an achievement, but if it is simply an arbitrary barrier, the desire to cross it decreases along with the reader’s interest in the story. However, I would argue that without the narrative curtain, a player’s desire to make a line of IF’s web suffers serious attrition. If the text simply sprawls out before the reader with no particular narrative thrust, IF becomes less powerful and engaging than traditional fiction. However, the curtain still remains on the level of input, and if the text presents a world for the player to explore, the reader’s desire to discover the intricacies of that world erects yet another form of the narrative curtain — the allure of textual frontier, of undiscovered country. I would argue that the barrier of the narrative curtain is IF’s analog to the element of conflict in traditional narratives — a text can exist without it, but that existence is a dull one indeed.

A further effect of the narrative curtain is its impact on narrative time. The reason why an IF text can take “weeks, even months” to complete is because it takes time to discover how to pass through the various curtains it constructs for its reader, and the program won’t allow its reader to continue until she has discovered the secret of its puzzle. In other words, unlike readers of a traditional narrative, IF players can’t turn the page until they “deserve” to, that worthiness being earned by puzzle-solving. Computer fictions can adjust narrative time not only through forcing the reader to wait for blocks of text, but by challenging him to pass tests before the story can continue.

This brings up another salient point about IF — the frustration it causes when its reader finds herself unable to solve the puzzle. Nearly every player of Infocom games has experienced the sensation of being “stumped.” In the practical arena this has translated into hint book sales for Infocom, Inc. But what of IF theory? I would suggest that when the narrative curtain becomes impenetrable, IF is in its greatest danger of becoming unfriendly to the reader. The player is likely to simply stop playing if the obstacles become too difficult, allowing the curtain to become permanent and leaving the reader with a frustrating sense of lack of closure. However, there are important caveats to this point. Randall articulates the first:

Even when the reader cannot formulate a solution to advance the interactive text, she can usually back-track to a previous screen or side-step to another… In backtracking, the reader re-reads portions of the text, often many times over, in an effort to find a clue that will allow the barrier to be breached. By side-stepping, the reader hopes to return to the barrier with a new sense of how to surmount it. In either case, what is continuous is not the plot but rather the development of the reader’s knowledge of the world in which her character is travelling. (190)

The other point is that even when the reader leaves the program, the narrative curtain still possesses power. Players often return to a puzzle which is stumping them after weeks or months of inactivity, whenever a new approach occurs to them. When these are the circumstances and the curtain finally is pierced, the satisfaction of achievement is proportionally heightened.

The notion of the narrative curtain brings out one of the most interesting features of IF, its casting of the reader as bricoleur. The closest analog to this casting in traditional texts is in the mystery novel, where the reader often watches actively for clues in order to beat the textual detective to the solution of the crime, gaining thereby a certain sense of satisfaction and even superiority. However, in a mystery novel the answer will be revealed as long as the reader keeps reading. IF, on the other hand, forces the player to collect and combine pieces of the text and recontextualize them in order to pass through the narrative curtain, even if that bricolage is as simple as finding a key for a locked door. Until the player makes the connections the program wants, the Quest simply will not progress, though the line of the story may continue.

THE INTERACTIVE SUBJECT

The question of reader subjectivity is already incredibly complicated, and the advent of IF only adds more questions rather than answering any of those already extant. Thus, this section can only scratch the surface of this intriguing question, but I hope to address some of the main points.

Georges Poulet addresses questions of subjectivity in his essay “Criticism and The Experience of Interiority,” and brings up a point which is useful to the analysis of IF: through the medium of language, both author and reader are forced by the limited nature of their communication to exclude their actual lives and take on the “roles” which the language demands. Of course, the reader’s adjustment is greater because the author is choosing the words while the reader is making sense of them. IF texts complicate the assumption of such “roles.” Since the player is the direct agent of action in the story, one could argue that he is more himself than when reading a traditional text. However, this argument has a complicated flip side.

First of all, the reader’s subjectivity is constrained by the inevitable limits of the parser. Thus when I engage with Zork I am forced into the role of someone who cannot use certain words (the vast majority of words, actually). Moreover, the Quest structure demands that its readers assume the role of someone who cares about completing the task at hand. Thus, Zork asks me to become someone who would kill trolls and remove treasures from an underground labyrinth. Further, IF settings are often quite removed from reality, demanding another role adjustment, belief in hyperspace or magical mushrooms, for example. Finally, the text sometimes forces the player into a more specific persona. In Infidel, for example, the reader’s character is a ruthless, greedy archaeologist who is deserted at the narrative’s outset by his underpaid and overworked crew. Plundered Hearts, an interactive romance set in the 18th century, casts the player as a young woman who is captured by pirates. This role-casting can become highly specific, as in Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy, where the player is cast as Arthur Dent, the protagonist of the Douglas Adams novel from which the game is adapted. Other games however, allow interactive adjustment of the player’s role. Beyond Zork, for example, allows the player to create a “character”, which she names and for which she chooses the degrees of six different attributes (strength, compassion, etc.) from a fund of percentage points. Bureaucracy asks the player to fill out a form listing certain vital statistics (name, address, boy/girlfriend, age, etc.) and then further confounds that player’s subjectivity by forcing him into a specific situation with little or no bearing on reality and using the statistics provided to torment the player’s persona (The boy/girlfriend runs off, etc.)4

I would argue that no matter what the level, the player of IF texts is forced to some degree to assume the type of role which Poulet asserts for traditional texts. This role is further enforced by the program’s second person singular mode of address. When a typical sentence of IF is “You can’t go that way,” it’s clear that the text enacts an enforced recontextualization on the reading subject. This is where postmodern theories of subjectivity present themselves as useful tools for examination of the interactive subject. Postmodern theory generally accepts the subject as already fragmented, a fragmentation which is easy to see in the interactive subject. I would suggest that readers of IF texts, especially while they are in the process of reading, are excellent examples of “cyborgs,” as Donna Haraway uses the term. In “A Manifesto For Cyborgs” Haraway argues that the distinction between human and machine has already become so blurred that we experience day to day life as cyborgs, thinking of mechanical devices as extensions of our own subjectivity. For the IF player, reading a computer screen and typing English commands on a keyboard in order to direct a mystery narrative in the persona of Dr. Watson, this assertion isn’t difficult to accept.

INTENDED, IMPLIED, AND IDEAL READERS

The nascent stages of the formation of reader-response criticism were characterized by theorists like Walker Gibson and Gerald Prince, who constructed theories of readership which attempted to complicate the idea of reader reception by suggesting that texts ask readers to adjust their own perceptions of reality in order to conform to textual paradigms. We have already seen that IF forces a complicated and fragmented subjectivity on its reader, and examination of Gibson’s and Prince’s theories can help us to better understand this process.

Gibson, in “Authors, Speakers, Readers, and Mock Readers,” postulates a “mock reader,” arguing that “every time we open the pages of another piece of writing, we are embarked on a new adventure in which we become a new person — a person as controlled and definable and as remote from the chaotic self of daily life as the lover in the sonnet” (1). IF seems to literalize this process, while complicating it with the question of player agency. Although the player does assume a certain role, she also directly controls the actions of that persona. Thus, like traditional texts, IF constructs a niche into which the player must force herself, but within that niche she is allowed a freedom of movement unheard of in traditional texts.

Gerald Prince’s article “Introduction to the Study of the Narratee” introduces (appropriately enough) his concept of the narratee, “the narratee being someone whom the narrator addresses” (7). Prince goes on to use this concept to subdivide the types of readers. He distinguishes the real reader, the individual with the book in his hands, from the virtual reader, the intended audience of the author. He also posits an ideal reader, who would theoretically have a perfect understanding of the text in all its nuances. This ideal reader is, of course, a fiction. The narratee is separate from of these, though it incorporates elements of each. Like Gibson’s “mock reader” the narratee is someone who the real reader becomes in the process of reading. Since the narratee is the person to whom the narrative is directed, the text itself dictates the narratee.

These classifications are intriguing, but IF demands not only new categories but new scrutiny of the old ones. I would suggest three basic categories which have the mnemonic advantage of all starting with the same letter: Intended, Implied, and Ideal readers. The Ideal reader of an IF text is just as fictional as the one Prince stipulates. An Ideal reader would know the entire vocabulary of the parser, understand immediately how to pass through each narrative curtain, and appreciate every aspect and nuance of the interactive text. The Intended reader, on the other hand, while still a fictional construct, is more firmly within the realm of possibility. Intended readers are who the author of the IF text had in mind as average consumers. They would be able to appreciate the text and solve the puzzles, and would hit on some of the IF’s features, but would still leave some narrative curtains standing, and may miss some textual nuances. Implied readers are analogous to mock readers and narratees; they are the reader-personas to whom the narrative is directed. The text makes certain assumptions about them, such as their fluency in English and their basic grasp of textual conventions, but none about their ability to pass through narrative curtains or to grasp textual nuances. Each of these readers is a fictional construct, and together they form a continuum, from Ideal to Implied, into which the real reader necessarily must fall.

The advantage of this system of classification is not so much in its accuracy, but in its utility for further complicating questions of authorship and intentionality. For example, one problem with the Ideal reader is that, although she would grasp textual nuances perfectly, her perfect ability to instantly pierce narrative curtains would detract from her overall interactive reading experience. I would argue that part of the pleasure of the text lies in the challenge of bricolage which it issues the reader, and if solving the puzzles is no challenge, then that pleasure is drastically decreased. The Implied reader, on the other hand, while he may be familiar with basic conventions of IF, may also be immediately stumped or may disagree violently with the ideological content of the text. Thus, the “narratee” of IF may in fact be alienated by the text to an even greater degree than he would be by a traditional fiction.

Furthermore, the idea of intentionality is a highly dubious one, and even more so in IF. If we accept that traditional fictions are created by readers in conjunction with texts, as reader-response critics assert, then the author drops out of the picture. IF encourages this process through the tendency of computer software publishers to elide the names of programmers. More importantly, however, the notion of intentionality receives a staggering blow from the basic form of the text: one which refuses to acknowledge itself as complete until the reader fills in its gaps.

FILLING IN ISER’S GAPS

The notion of the narrative gap was first articulated by Wolfgang Iser. In “The Reading Process: A Phenomenological Approach,” Iser asserts that “a literary text must therefore be conceived in such a way that it will engage the reader’s imagination in the task of working things out for himself, for reading is only a pleasure when it is active and creative” (51). If this sounds remarkably like IF theory, the reason is that Iser conceived of reading as an active, creative process, whose agent is continually filling in the blanks for the text. Iser finds these blanks, or “gaps”, in areas of the text which somehow thwart our preconceived expectations: “whenever the flow is interrupted and we are led off in unexpected directions, the opportunity is given to us to bring into play our own faculty for establishing connections — for filling in the gaps left by the text itself” (55). I would argue that this description still applies to IF — the blocks of text in an IF program are just as capable of producing such moments of unexpectedness as any in print fiction.

However, IF obviously adds another level to the notion of gaps in a text. As Randall points out, “interactive fiction displays two types of narrative gap: the traditional type filled unconsciously by the reader, and a manifest type shown on the computer’s screen” (189). Every time the reader sees a prompt, she is expected to input some command, without which the story is simply halted. This prompt, this halting, is clearly a new type of narrative gap, one which the reader fills in more literally than Iser ever imagined.5 Iser assumes that readers of traditional texts always imaginatively fill in the gaps left by the text at its unexpected moments. IF, however, goes one step further, by forcing an active reading. It is this forceful narrative gap which makes IF so friendly to analysis in reader-response models. Far more than in a traditional text, the reader must respond if the text is to continue to reveal itself. Moreover, that response must consist of elements which the text can parse, or else the reader receives a message like “I don’t know the word ‘deconstruct'” (for example) and is returned to the prompt.

Iser uses the metaphor of constellations to clarify his theory: “two people gazing at the night sky may both be looking at the same collection of stars, but one will see the image of a plough, and the other will make out a dipper. The ‘stars’ in a literary text are fixed; the lines that join them are variable” (57). Iser’s stars are the printed units of language, and his lines are the conscious or unconscious connections drawn by the reader. I would contend that IF adds even more resonance to this metaphor. The reader of IF not only draws the connections Iser refers to, but activates explicit connections between textual blocks at every prompt, creating her own unique “constellation” of narrative, one whose shape clearly manifests itself in the line of the story under her guidance.

IDENTITY THEMES IN IF

If IF indeed helps to extricate and document the ways in which readers fill in narrative gaps, what can we learn from the differences in the constellations they create? One theory which presents itself as useful for answering this question is the one presented by Norman Holland in “UNITY IDENTITY TEXT SELF”. In that essay, Holland argues that unity and text have an analogous relationship to identity and self, the former term in each pair being an abstraction from patterns evidenced by the latter term. He argues further that because we are each possessed of and immersed in an identity, we extrapolate textual unity according to certain themes inherent in that identity (and the same applies to our extrapolations of the identities of others). For Holland, reading is a process in which, the pieces of self interlock with the pieces of text to form a reading, an interpretation of text which is inevitably stamped with the reader’s “identity theme.” Under this paradigm, interaction with an Infocom game operates like zipping up a zipper — the self and text interpenetrate to form a seamless narrative line, the direction of which must indicate elements of the reader’s identity theme.

However, there is a definite danger of oversimplification in this model. For one thing, no two readings of an interactive text, even by the same reader, are exactly the same. This fact calls into question the notion that identity themes can be traced even when the reading process is made more visible. In fact, it seems entirely plausible to me that the varying narrative lines of the interactive process are part of another binarism analogous to those Holland discusses. Rather than a pattern which shows itself in one reading, the visible identity theme evoked by IF is more accurately (I would argue) an extrapolation of tendencies within a grouping of several narrative lines from the same reader. Thus, as identity is to self and unity is to text, so the visible identity theme is to the group of narrative lines.

Moreover, Holland’s model allows no room for change. I would argue that the experience of interactive fiction has a direct effect on the reader, and that the crossing of a narrative curtain drastically affects the next reading of that same situation. Once I’ve discovered, for example, the secret of the Echo Room in Zork, I am highly unlikely to spend as much time there as when I was trying to puzzle it out. Conversely, the crossing of narrative curtains often allows the text to expand, showing the reader new locations or new features. It seems plausible to me that the text and player of IF can be read as providing growth stimuli for each other. Thus interactive fiction is a mutual growing experience, not only for the reader, but for the text as well, and the result of such a reading is not a text imprinted with the reader’s identity theme or a reader stamped with the themes of the text, but a unique collaboration of reader and text, one which partakes from both in order to create an unprecedented result.

READING AND WRITING: OBSOLETE CATEGORIES?

As we progress further and further into theorizing IF, it becomes increasingly clear that notions of authorship and readership are becoming more and more difficult to define. It is at this point when the theories most useful to us are those of the paradigmatic theorist of reader-response criticism, Stanley Fish. “Literature in the Reader: Affective Stylistics” was the article which announced Fish’s perspective on the reading process, a perspective which has come to be identified almost programmatically with reader-response criticism. In it, Fish posited meaning as an event, a “making sense” enacted by the reader. By closely reading sentences, and analyzing their capacities for forming meaning in a temporal dimension through the succession of words, Fish showed that meaning is not extracted from a text as if every word in it were received simultaneously. Fish analyzed the dynamics of expectation to demonstrate meaning as a sequence of mental events. His article attempted to change the typical critical question “What does this sentence mean?” to “What does this sentence do?”

I would argue that in the creation of an IF narrative, both the author and the reader are continually asking themselves this crucial question. Authors of interactive fiction write with the consciousness of their medium. They are aware of the narrative’s enforced gaps, and of the narrative curtains they are constructing, and this awareness inevitably affects their writing. For example, text in IF often contains hints about how to pass through certain narrative curtains. The magpie in the passage from Trinity I quoted at the beginning of this paper is squawking part of a formula by which the player may pass through a crucial narrative curtain. Without the magpie’s help, the bricoleur/player would have no idea how to cross this juncture in the narrative. Those sentences were clearly constructed with a mind towards what function they would serve, what they would do. Players of IF texts confront the same question at every prompt. The player typing commands into the computer is forced to continually ask herself “What will this sentence do?” so that she may better communicate with the program. The experience of writing for a parser provides constant reminders of authorship, audience, and action of units of language. It forces upon us the question which Fish only asserts.

The answers to this question seem to show up more clearly in interactive fiction, but this appearance itself is highly dubious. Though authors discover the effect of their sentences on game testers, they obviously cannot learn this effect for every player at every juncture. In fact, since meaning is created through the interaction of player and text rather than player and author, the author’s thoughts become irrelevant. It is the text which ultimately asks the crucial questions. Conversely, though the player always sees the results of his commands, they are not always clear or easily interpreted. While the text usually guides or blocks input, it occasionally does both, and sometimes does neither, producing a response like “Try to phrase that another way.” Though both player and text are asking “What will this sentence do?” the answer is neither easy nor clear.

This is where Fish’s notion of interpretive strategies comes into play. In “Interpreting the Variorum,” Fish asserts that “Texts are written by readers, not read, since, the argument now states, the formal features of the text, the authorial intentions they are normally taken to represent, and the reader’s interpretive strategies are mutually interdependent” (Tompkins xxii). Fish’s argument for traditional texts must be modified a little for IF, because the form muddies the distinction between author and reader. Not only is the reader utilizing interpretive strategies, the text is as well, and furthermore those strategies must coincide if the narrative is to progress. For a narrative curtain to be drawn, the reader needs to have a strategy which will allow her the correct pieces for her bricolage, and the text must have a strategy with which to interpret the player’s input. In this paradigm, the player and computer together fit rather well into Fish’s concept of the “interpretive community,” “made up of those who share interpretive strategies not for reading (in the conventional sense) but for writing texts, for constituting their properties and assigning their intentions” (“Variorum” 182).

However, to truly accept this concept, it is crucial that we absorb one final ideological prop, the notion of self as text as advanced by Walter Benn Michaels in “The Interpreter’s Self: Peirce on the Cartesian ‘Subject'”. In Michaels’ interpretation of the pragmatic philosophy of Charles Sanders Peirce, “our minds are accessible to us in exactly the same way that everything else is. The self, like the world, is a text” (199). Once we accept this dictum, several previously unsettling aspects of IF finally fall into place. First of all, if we can read the self as a text, we can just as easily read the text as a kind of self, especially the text of IF, which actively seeks input. With this understanding, interactive textuality is thrust into a new light. In the interaction of the computer program’s self/text with the player’s self/text, there is no reader and writer. They read and write each other. In the radical realm of interactive fiction, the theories of reader-response critics become facts, and in fact are surpassed. Not only does the reader actively fill in textual gaps, but the text fills gaps in the reader, plants seeds for ideas which haven’t come yet. Human and computer, when both are understood as both self and text, become a true interpretive community, each community producing its own unique fictions.

“Reader” and “text” become provisional terms. The text is a reader just as the reader is a text. Even “player” and “program” are problematic. The IF is, after all, attempting to program its human reader into certain responses, and is doing so with a significant element of playfulness. Interactive fiction, by enacting reader-reception theory, has stripped the most basic terms of literature of their apparent meaning, and cast us into a new location. It is one which is alien and unfamiliar, but it is also a nexus from which radiate thousands of branches of possibility.6

Endnotes

1 Because of its utility and clarity, I here reprint and appropriate for my own use Neil Randall’s definition of a “traditional” text:

Throughout this article I will use the term “traditional” to refer to literature printed on paper, usually in book (rather than magazine) format. I considered such terminology as “book fiction” or “Gutenberg literature” to avoid collocating such diverse novels as Mitchell’s Gone With The Wind and Barth’s Sabbatical, which have in common only the fact that they are written by Americans and printed on paper, but such terminology proved more cumbersome than it was worth. “Traditional”, therefore, says nothing of the degree to which a work is or is not avant-garde; it is simply a reference to medium. (190)

[Back to reference]

2 The sources of the programs I refer to are two anthologies of Infocom programs, The Lost Treasures Of Infocom volumes I and II. Since these packages contain a total of 31 texts, I find it easier to simply cite the collection than each individual text.

[Back to reference]

3 My analysis of the shape of IF owes much to theories developed for hypertext, a type of computer construction related, but not identical to, IF, the primary difference being that hypertext’s method of branching involves “clicking” with a mouse on a significant word or phrase rather than typing words for a parser. Discussions of hypertext which are useful for analysis of IF are included in my list of references.

[Back to reference]

4 Other games vary the persona of the reader even within the context of the program. Border Zone, for example, is divided into “chapters,” each of which casts the reader in a new character.

[Back to reference]

5 However, even this literalization is problematic due to the fact of the parser. I would argue that Fish’s notion of societally mediated boundaries to interpretation comes in handy here. Just as the reader’s imagination is not free to fill in the gaps in just any way, so the player’s input is restricted by certain ambiguous boundaries.

[Back to reference]

6 This paper only attempts to examine IF as it looks through the lens of reader-response criticism. A more complete discussion of IF would include sections on the idea of the varying levels of code inherent in reading an IF text, some system for evaluating quality, a consideration of the political implications of simulation, questions that still remain open, and of course the obligatory “speculation on the future” section. I had originally planned on these, but the project simply became too large. When I revise this paper to turn it into an article, those sections will be included. [LOL Yeah, right. That never happened. –PO 2000]

[Back to reference]

References

Bolter, Jay David. “Literature in the Electronic Writing Space.” In Myron C. Tuman (ed.), Literacy Online: The Promise (and Peril) of Writing With Computers. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992: 19-41

Campbell, P. Michael. “Interactive Fiction and Narrative Theory: Towards An Anti-Theory.” New England Review and Bread Loaf Quarterly 10.1 (1987): 76-84

Fish, Stanley. “Interpreting the Variorum.” In Jane Tompkins (ed.), Reader-Response Criticism: From Formalism To Post-Structuralism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980: 164-184

Fish, Stanley. “Literature In The Reader: Affective Stylistics.” In Jane Tompkins (ed.), Reader-Response Criticism:From Formalism To Post-Structuralism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980: 70-100

Gibson, Walker. “Authors, Speakers, Readers, and Mock Readers.” In Jane Tompkins (ed.), Reader-Response Criticism: From Formalism To Post-Structuralism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980: 1-6

Haraway, Donna. “A Manifesto For Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980’s.” Socialist Review 80 (1985): 65-107

Holland, Norman N. “UNITY IDENTITY SELF TEXT.” In Jane Tompkins (ed.), Reader-Response Criticism: From Formalism To Post-Structuralism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980: 118-133

Infocom. The Incomplete Works of Infocom, Inc. (advertising pamphlet) Cambridge: Infocom, 1985

Infocom. The Lost Treasures Of Infocom. Cambridge: Infocom, 1992

Infocom. The Lost Treasures Of Infocom II. Cambridge: Infocom, 1992

Infocom. You Are About to See The Fantastic Worlds Of Infocom Unfold Before Your Very Eyes. (advertising pamphlet) Cambridge: Infocom, 1984

Iser, Wolfgang. “The Reading Process: A Phenomenological Approach.” In Jane Tompkins (ed.), Reader-Response Criticism: From Formalism To Post-Structuralism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980: 50-69

Kelly, Robert T. “A Maze of Twisty Little Passages, All Alike: Aesthetics and Teleology in Interactive Computer Fictional Environments.” Science Fiction Studies 20 (1993): 52-68

Landow, George P. Hypertext: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992

Michaels, Walter Benn. “The Interpreter’s Self: Peirce on the Cartesian ‘Subject’.” In Jane Tompkins (ed.), Reader-Response Criticism: From Formalism To Post-Structuralism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980: 185-200

Moulthrop, Stuart. “Reading From The Map: Metonymy and Metaphor In The Fiction of ‘Forking Paths’.” In Paul Delany and George P. Landow (eds.), Hypermedia and Literary Studies. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991: 119-132

Moulthrop, Stuart and Nancy Kaplan. “Something to Imagine: Literature, Composition, and Interactive Fiction.” Computers And Composition 9.1 (1991): 7-23

Niesz, Anthony J. and Norman N. Holland. “Interactive Fiction.” Critical Inquiry 11.1 (1984): 110-29

Poulet, Georges. “Criticism and The Experience of Interiority.” In Jane Tompkins (ed.), Reader-Response Criticism: From Formalism To Post-Structuralism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980: 41-49

Prince, Gerald. “Introduction To The Study Of The Narratee.” In Jane Tompkins (ed.), Reader-Response Criticism: From Formalism To Post-Structuralism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980: 7-25

Randall, Neil. “Determining Literariness In Interactive Fiction.” Computers and the Humanities 22 (1988): 183-91

Tompkins, Jane. “An Introduction To Reader-Response Criticism.” In Jane

Tompkins (ed.), Reader-Response Criticism: From Formalism To Post-Structuralism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980: ix-xxvi

Ziegfeld, Richard. “Interactive Fiction: A New Literary Genre?”. New Literary History 20.2 (1989): 341-372