IFDB page: Zork Zero

[This review contains lots of spoilers for Zork Zero, as well as at least one for Zork I. Also, I wrote an introduction to these Infocom >RESTART reviews, for those who want some context.]

The earliest game in the Zork chronology was one of the latest games in the Infocom chronology. Zork Zero emerged in 1988, two years after the company was bought by Activision, and one year before it would be shut down. Zork was Infocom’s most famous franchise by far, and this prequel was the company’s last attempt to milk that cash cow, or rather its last attempt with original Implementors on board. Activision-produced graphical adventures like Return to Zork, Zork: Nemesis, and Zork: Grand Inquisitor were still to come, but those were fundamentally different animals than their namesake. Zork Zero, written by veteran Implementor Steve Meretzky, was still a text adventure game.

However, there was a little augmentation to the text this time. Along with a few other games of this era, Zork Zero saw Infocom dipping its toe into the world of graphics. The text window is presented inside a pretty proscenium arch, one which changes its theme depending on your location in the game, and also provides a handy compass rose showing available exits. Some locations come with a thumbnail icon, many of which are pretty crudely pixelated, but some of which (like the Great Underground Highway) are rather memorable. Most crucially, several important puzzles and story moments rely upon graphics in a way that hadn’t been seen before in a Zork game, or any Infocom game for that matter. In order to make these nifty effects work in Windows Frotz, our interpreter of choice, Dante and I had to do a bit of hunting around in the IF Archive — thus it was that we solved our first puzzle before we even began the game.

>EMBIGGEN ZORK. G. G. G. G.

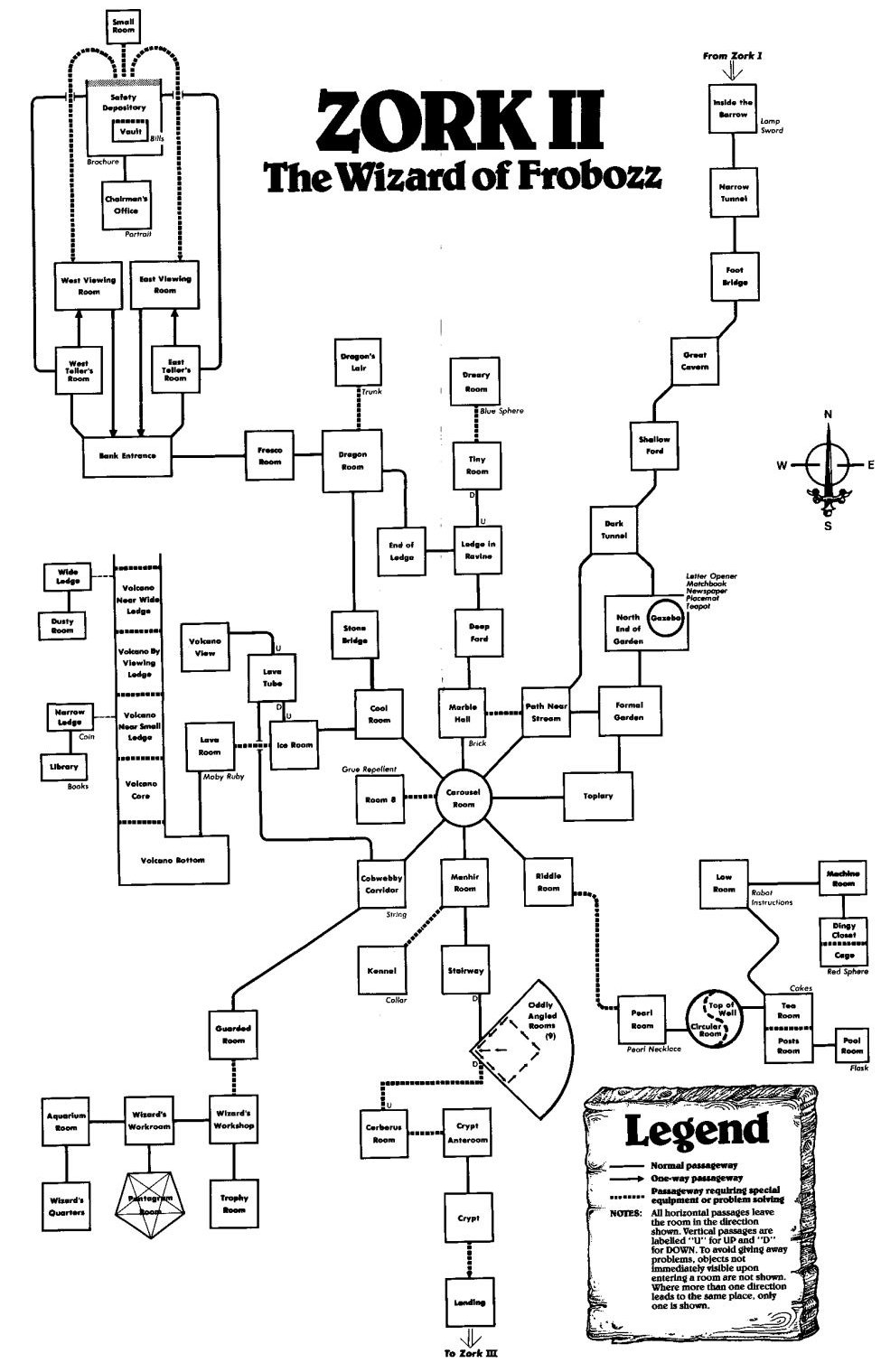

Once we did start, we found that graphics weren’t the only way Meretzky found to expand on the Zork legacy. He also expanded on it by… expanding it! Over and over again, we were knocked out by the scope of this game. It’s enormous! Our Trizbort map had 208 rooms, and that’s not even counting ridiculous location “stacks” like the 400-story FrobozzCo building or the 64-square life-sized chessboard. By contrast, our map for Zork I had 110 rooms, and Zork III had a meager 59. So many locations. So many puzzles. So many objects. So many points! You’ll score a thousand hard-won points in a successful playthrough of Zork Zero. Dimwit Flathead’s excessiveness is a frequent butt of Meretzky’s jokes in this game (e.g. a huge kitchen that “must’ve still been crowded when all 600 of Dimwit’s chefs were working at the same time”), but if Dimwit were to design an IF game, it would definitely be this one.

The largesse still doesn’t apply to writing noun descriptions, though. For example:

>X CANNONBALL

There's nothing special about the cannonball.

>X UNICORNS

There's nothing unusual about the herd of unicorns.

>X FJORD

It looks just like the Flathead Fjord.

Even this late in Infocom’s development, they still hadn’t adopted the ethos that the most skilled hobbyists would take up later, of enhancing immersion by describing everything that could be seen.

Similarly, inventory limits are still around to vex us, and they hit especially hard in a game like this, which is absolutely overflowing with objects. Because of those limits, we followed our tried-and-true tactic of piling up all our spare inventory in a single room. In the case of Zork Zero, we knew we’d be throwing a bunch of those objects into a magic trophy case cauldron, so we stacked them in the cauldron room. By the time we were ready for the endgame, that room’s description was pretty hilarious:

Banquet Hall

Many royal feasts have been held in this hall, which could easily hold ten thousand guests. Legends say that Dimwit's more excessive banquets would require the combined farm outputs of three provinces. The primary exits are to the west and south; smaller openings lead east and northeast.

A stoppered glass flask with a skull-and-crossbones marking is here. The flask is filled with some clear liquid.

A 100-ugh dumbbell is sitting here, looking heavy.

Sitting in the corner is a wooden shipping crate with some writing stencilled across the top.

A calendar for 883 GUE is lying here.

You can see a poster of Ursula Flathead, a four-gloop vial, a shovel, a box, a spyglass, a red clown nose, a zorkmid bill, a saucepan, a ring of ineptitude, a rusty key, a notebook, a harmonica, a toboggan, a landscape, a sapphire, a glittery orb, a smoky orb, a fiery orb, a cloak, a ceramic perch, a quill pen, a wand, a hammer, a lance, an easel, a wooden club, a bag, a silk tie, a diploma, a brass lantern, a notice, a broom, a funny paper, a stock certificate, a screwdriver, a gaudy crown, a ticket, a dusty slate, a treasure chest, a blueprint, a saddle, a fan, a steel key, a walnut shell, a manuscript, an iron key, a package, a T-square, a fancy violin, a metronome, a scrap of parchment, a proclamation, a cannonball, a sceptre and a cauldron here.

That certainly wasn’t everything, but you get the idea.

In fact, this game was so big that its very size ended up turning into a puzzle, or at least a frustration enhancer. Dante and I flailed at a locked door for quite a while before realizing that we’d had the key almost since the beginning of the game. We forgot we’d obtained an iron key by solving a small puzzle in one of our earliest playthroughs, and the key itself was lost in the voluminous piles of stuff we had acquired. When we finally realized we’d had the key all along, it was nice to open up the door and everything, but it also felt a bit like we should be appearing on the GUE’s version of Hoarders.

Not only did the scope of Zork Zero obscure the answers to puzzles like that, it also functioned as a near-endless source of red herrings. It’s possible to waste immense amounts of time just checking locations to see if you’ve missed anything, because there are just so many locations. The FrobozzCo building was of course an example of this, but even more so was the chessboard, which soaked up tons of our time and attention trying to figure out what sort of chess puzzle we were solving. Not only was exploring the whole thing a red herring, but so was making moves and doing anything chess-related!

On the other hand, the game’s sprawling vistas can also evoke a genuine sense of awe, somewhat akin to seeing the Grand Canyon from multiple viewpoints. There was a moment in the midgame where we’d been traversing a very large map to collect various objects, and then the proper application of those objects opened up a dimensional gateway to an entirely new very large map. Shortly afterward, we realized that in fact, the puzzle we’d just solved had in fact opened up five different dimensional gateways, some of which eventually connected to our main map but many of which did not! Moments like that were breathtaking, not just because of all the authorial work they implied, but also because of the gameplay riches that kept getting laid before us.

Sometimes, to make things even sillier, the effects of the giant inventory would combine with the effects of the giant map. One of those offshoot maps mentioned above contained a special mirror location, which would show you if there was anything supernatural about an object by suggesting that object’s magical properties in its reflection. Super cool, right? Well yeah, except that inventory limits, combined with incredible object profusion, required us to haul a sliver of our possessions during each trip to the mirror, and each trip to the mirror required a whole bunch of steps to accomplish. (Well, there was a shortcut through a different magical item, but we didn’t realize that at the time, and in fact only caught onto that very late in the game, so didn’t get much of a chance at optimization.)

So yes, the mirror location was a wonderful discovery. Less wonderful: hauling the game’s bazillion objects to the mirror in numerous trips to see if it could tell us something special. But then when we found something cool that helped us solve a puzzle: wonderful! This is quintessential Zork Zero design — an inelegant but good-natured mix of cleverness, brute force, and sheer volume. The capper to this story is that there’s one puzzle in particular that this mirror helps to solve, but we fell prey to Iron Key Syndrome once again and somehow failed to bring that puzzle’s particular objects (the various orbs) to the mirror, obliging us to just try every single one orb in the puzzle until we found the right one.

>RECOGNIZE ZORK TROPE. G. G. G. G.

Those orbs felt pretty familiar to us, having just recently palavered with Zork II‘s palantirs. (Well, the game calls them crystal spheres, but c’mon, they’re palantirs. Or, as Wikipedia and hardcore Lord of the Rings people would prefer, palantíri.) However, familiar-looking crystal balls were far from the only Zork reference on hand. As I said, Zork Zero appeared late in Infocom’s history, and with the speed at which the videogame industry was moving, Zork I had for many already acquired the reflected shine of a bygone golden age. Thus, nostalgia was part of the package Infocom intended to sell with this game, which meant Zork tropes aplenty.

One of the best Zorky parts of the game concerns those dwellers in darkness, the lurking grues. In the world of Zork Zero, grues are a bygone menace. As the in-game Encyclopedia Frobozzica puts it:

Grues were eradicated from the face of the world during the time of Entharion, many by his own hand and his legendary blade Grueslayer. Although it has now been many a century since the last grue sighting, old hags still delight in scaring children by telling them that grues still lurk in the bottomless pits of the Empire, and will one day lurk forth again.

Oh, did I fail to mention that this huge game also contains an interactive Encyclopedia Frobozzica, with dozens of entries? Yeah, this huge game also has that. In any case, “the bottomless pits of the Empire” might sound familiar to longtime Zork players, or to readers of Infocom’s newsletter, which was for several years called The New Zork Times, until a certain Gray Lady‘s lawyers got involved. As NZT readers would know, there was a time before Zork was on home computers, before it was even called Zork at all. It was called Dungeon, at least until a certain gaming company‘s lawyers got involved.

In Dungeon, there were no grues in the dark places of the game, but rather bottomless pits — a rather fitting fate for someone stumbling around in a dark cave, but the game was more than just a cave. As the NZT tells it:

In those days, if one wandered around in the dark area of the dungeon, one fell into a bottomless pit. Many users pointed out that a bottomless pit in an attic should be noticeable from the ground floor of the house. Dave [Lebling] came up with the notion of grues, and he wrote their description. From the beginning (or almost the beginning, anyway), the living room had a copy of “US News & Dungeon Report,” describing recent changes in the game. All changes were credited to some group of implementers, but not necessarily to those actually responsible: one of the issues describes Bruce [Daniels] working for weeks to fill in all the bottomless pits in the dungeon, thus forcing packs of grues to roam around.

Sure enough, in Zork Zero prequel-ville, when you wander into a dark place, you’ll get the message, “You have moved into a dark place. You are likely to fall into a bottomless pit.” In fact, at one of the lower levels of the enormous map, we found a location called “Pits”, which was “spotted with an incredible quantity of pits. Judging from the closest of them, the pits are bottomless.” Across the cavern, blocked by those pits, was “an ancient battery-powered brass lantern”, another major Zork nostalgia-carrier. Fittingly, to get to the traditional light object, we had to somehow deal with the even-more-traditional darkness hazard.

Lucky for us, yet another puzzle yielded an “anti-pit bomb”, which when thrown in the Pits location causes this to happen:

The bomb silently explodes into a growing cloud of bottomless-pit-filling agents. As the pits fill in, from the bottom up, dark and sinister forms well up and lurk quickly into the shadows. Uncountable hordes of the creatures emerge, and your light glints momentarily off slavering fangs. Gurgling noises come from every dark corner as the last of the pits becomes filled in.

Thereafter, when the PC moves into a dark place, the game responds with a very familiar message: “You have moved into a dark place. You are likely to be eaten by a grue.” Luckily, the game provides an inexhaustible source of light in the form of a magic candle, so there are no terrible light timers to deal with. Some things, nobody is nostalgic for.

Lack of a light timer made it easier to appreciate this game’s Wizard of Frobozz analogue, the jester. Like the Wizard, this guy pops up all over the place at random times, creating humorous magical effects which generally block or delay the PC. Sometimes those effects are themselves Zork references, such as when he sends a large deranged bat swooping down, depositing the PC elsewhere as it shrieks, “Fweep! Fweep!” Also like the Wizard, his effects get less funny the more they’re repeated. And also also like the Wizard, he figures prominently into the game’s plot.

However, unlike the Wizard, he functions in a whole bunch of other capacities as well. He’s the game’s primary NPC, appearing to deliver jokes, adjudicate puzzles (especially riddles), occasionally help out, congratulate solutions, and hang around watching the player struggle. He’s not quite an antagonist but certainly not an ally, and you get the sense he’s controlling far more than he lets on. In other words, he’s an avatar for the game itself, and in particular the twinkling eyes of Steve Meretzky.

>LAUGH. G. G. G. G.

Meretzky’s writing is witty and enjoyable throughout — it’s one of the best aspects of the game. He clearly revels in tweaking Zork history, as well as in reeling off line after line about the excessive Dimwit, e.g. “This is the huge central chamber of Dimwit’s castle. The ceiling was lowered at some point in the past, which helped reduce the frequency of storm clouds forming in the upper regions of the hall.” Probably my favorite Zork reference was also one of my favorite jokes in the game:

>HELLO SAILOR

[The proper way to talk to characters in the story is PERSON, HELLO. Besides, nothing happens here.]

Meretzky is also not above retconning previous bits of Zork lore that he disagrees with, such as his Encyclopedia Frobozzica correction of a detail in Beyond Zork‘s feelies: “The misconception that spenseweed is a common roadside weed has been perpetuated by grossly inaccurate entries in the last several editions of THE LORE AND LEGENDS OF QUENDOR.”

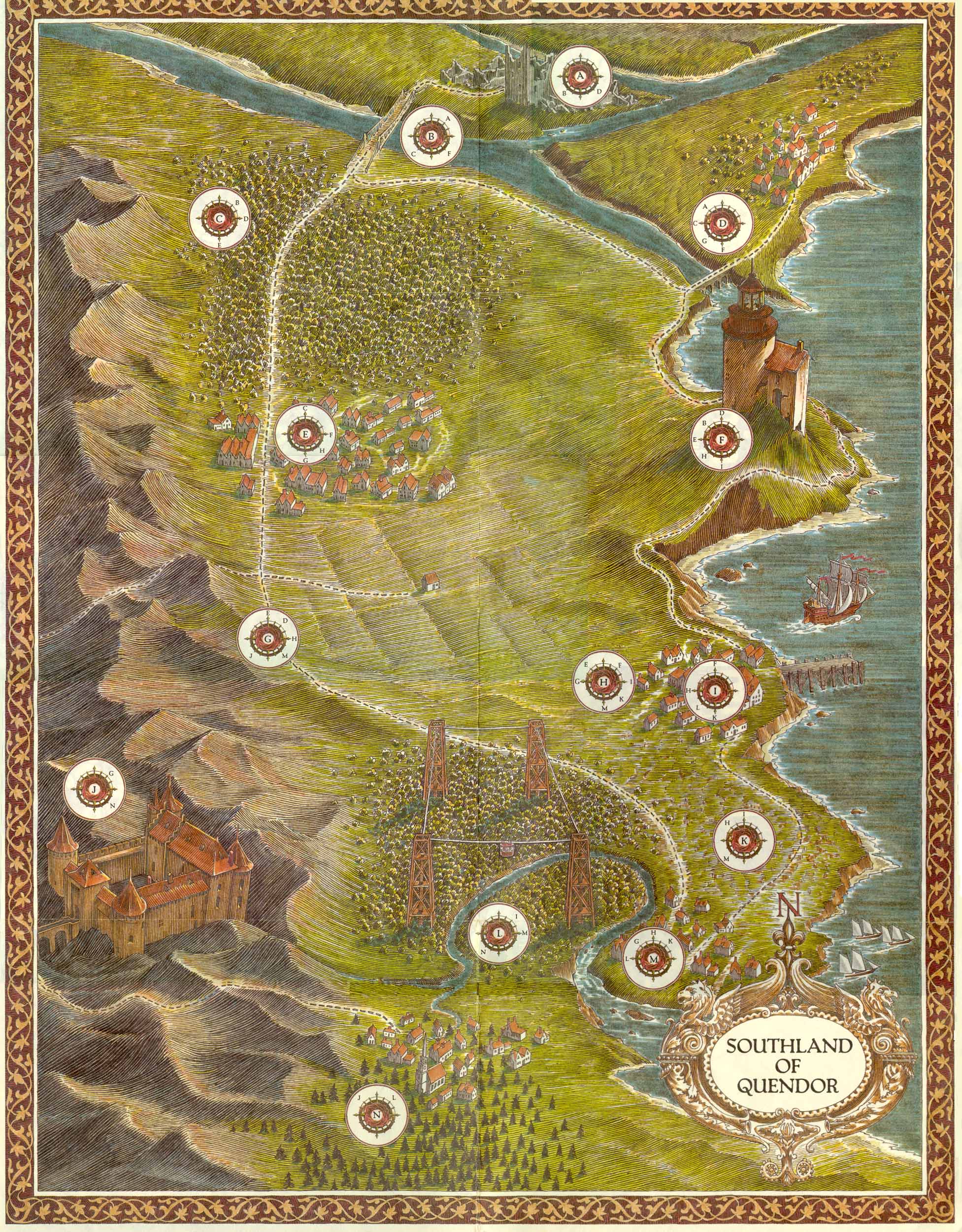

Speaking of feelies, this game had great ones, absolutely overflowing with Meretzky charm. Infocom was still heavily into copy-protecting its games via their documentation, and in typically excessive fashion, this game did that many times over, providing a map on one document, a magic word on another, and truckloads of hints (or outright necessary information) in its major feelie, The Flathead Calendar. This calendar called out to yet another aspect of Zork history, the wide-ranging Flathead family, with members such as Frank Lloyd Flathead, Thomas Alva Flathead, Lucrezia Flathead, Ralph Waldo Flathead, Stonewall Flathead, and J. Pierpont Flathead. The game’s treasures are themed around these figures, which was not only a lot of fun but also allowed me to do a bit of historical education with Dante, who still references Flatheads from time to time when mentioning things he’s learning in school.

The feelies establish a playful tone that continues through to the objects, the room descriptions, and the game’s general landscape. There are also great meta moments, such as the “hello sailor” response above, or what happens when you dig a hole with the shovel you find: “You dig a sizable hole but, finding nothing of interest, you fill it in again out of consideration to future passersby and current gamewriters.” Also enjoyable: the response to DIAGNOSE after having polymorphed yourself, e.g. “You are a little fungus. Other details of health pale in comparison.”

Meretzky even brings in a trope from Infocom’s mystery games, in probably the most ridiculous joke in the entire thing. There’s a location containing both a cannonball and a number of “murder holes”, “for dropping heavy cannonballs onto unwanted visitors”. This is obviously an irresistible situation, and the results are worth quoting in full:

>DROP CANNONBALL THROUGH HOLE

As you drop the cannonball through the murder hole, you hear a sickening "splat," followed by a woman's scream!

"Emily, what is it!"

"It's Victor -- he's been murdered!"

"I'll summon the Inspector! Ah, here he is now!" You hear whispered questions and answers from the room below, followed by footsteps on the stairs. The jester enters, wearing a trenchcoat and smoking a large pipe.

"I'm afraid I'm going to have to order Sgt. Duffy to place you under arrest, sir." You grow dizzy with confusion, and your surroundings swirl wildly about you...

Dungeon

A century's worth of prisoners have languished in this dismal prison. In addition to a hole in the floor, passages lead north, southeast, and southwest.

None of these characters (except the jester) occur anywhere in the game outside this response. Sergeant Duffy, as Infocom fans would know, is who you’d always summon in an Infocom mystery game when you were ready at last to accuse the killer. By the way, the Dungeon isn’t locked or anything — it’s a gentle joke, not a cruel one. The only real punishment is having to traverse the huge map to get back to wherever you want to be. I’ll stop quoting Meretzky jokes in a second, but I have to throw in just one more, because of the surprising fact that it establishes:

>EAT LOBSTER

1) It's not cooked. 2) It would probably bite your nose off if you tried. 3) You don't have any tableware. 4) You don't have any melted butter. 5) It isn't kosher.

Turns out the Zork adventurer (or at least the pre-Zork adventurer) is not only Jewish, but kosher as well! Who knew? Though, given that the kosher objection comes last, after lack of cooking, tableware, and butter, their commitment may be a bit halfhearted after all.

Amidst all the humor, Meretzky hasn’t lost his touch for pathos either, with a design that themes several puzzles around the sense of ruin and decay. For example, we found an instruction to follow a series of steps, starting from “the mightiest elm around.” In Zork Zero, this is an enormous tree stump. Meretzky has learned some lessons from Planetfall and A Mind Forever Voyaging about how to make a landscape that inherently implies its bygone better days. Even in the Zork prequel, the adventurer is traversing a fallen empire.

>REMEMBER PUZZLE. G. G. G. G.

Zork Zero isn’t just a prequel in narrative terms. As we kept finding old-timey puzzles like the rebus or the jester’s Rumpelstiltskin-esque “guess my name” challenge, Dante had the great insight that as a prequel, this game was casting back not just to an earlier point in fictional universe history, but to puzzle flavors of the pre-text-adventure past as well. Relatedly, as we ran across one of those vintage puzzles — The Tower of Hanoi Bozbar — he intoned, “Graham Nelson warned us about you, Tower of Bozbar.”

He was referencing a bit in Graham’s Bill of Player’s Rights, about not needing to do boring things for the sake of it: “[F]or example, a four-discs tower of Hanoi puzzle might entertain. But not an eight-discs one.” Zork Zero‘s tower split the difference by having six discs, and indeed tiptoed the line between fun and irritating.

However, if we’d been trying to do it without the graphical interface, the puzzle would have vaulted over that line. The game’s graphics are never more valuable than when they’re helping to present puzzles rooted in physical objects, like the Tower or the triangle peg solitaire game. Clicking through these made them, if not a blast, at least bearable. Those interactions do make for an amusing transcript, though — hilarious amounts of our game log files are filled with sentences like “You move the 1-ugh weight to the center peg” or “You remove 1 pebble from Pile #3” or “You are moving the peg at letter D.”

Just as some concepts are much easier to express with a diagram than with words, so are some types of puzzles much easier to express with graphics. Infocom had long been on the record as disdaining graphics, and indeed, I still think text has a scene-setting power that visuals can’t match. Meretzky’s descriptions of Dimwit’s excessive castle have more pith and punch than a visual representation of them could possibly muster. However, a picture is so much better than a thousand words when it comes to conveying a complex set of spatial relations. Even as early as Zork III‘s Royal Puzzle, Infocom leaned on ASCII graphics to illustrate those spatial relationships, because that just works so much better. Once they had more sophisticated graphics available, the range of Infocom’s puzzles could expand. It’s ironic that the first thing they did was to expand backwards into older puzzle styles, but then again it’s probably a natural first step into exploring new capabilities.

Going along with the overall verve of the game, those old chestnut puzzles revel in their old chestnut-ness. Zork Zero is a veritable toy chest of object games, logic challenges (e.g. the fox, the rooster, and the worm crossing the river), riddles, and other such throwbacks. Of course, there are plenty of IF-style puzzles as well. (There’s plenty of everything, except noun descriptions.) Sometimes these could be red herrings too — all the Zorky references kept leading us to believe we might see an echo of a previous Zork’s puzzle. Hence, for example, we kept attempting to climb every tree we saw, fruitlessly.

The IF parts of the game don’t hesitate to be cruel, either. I’ve mentioned that every single Zork game made us restart at some point — well Zork Zero was no exception. In this case, it wasn’t a light timer running out or a random event closing off victory, but simply using up an item too soon. We found a bit of flamingo food early in the game, and fed it to a flamingo… which was a mistake. Turns out we needed to wait for a very specific flamingo circumstance, but by the time we found that out, it was far too late. This flavor of forced-restart felt most like the experience we had with Zork I, where we killed the thief before he’d been able to open the jewel-encrusted egg. The difference is that restarting Zork Zero was a much bigger deal, because we had to re-do a whole bunch of the game’s zillion tasks.

On the other hand, while this game does have a maze, it is far, far less annoying than the Zork I maze. In general, the design of Zork Zero does a reasonably good job of retaining the fun aspects of its heritage and jettisoning the frustrating ones. Except for that inventory limit — interactive fiction wouldn’t outgrow that one for a while longer. And while there are a couple of clunkers among the puzzles (I’m thinking of the elixir, which is a real guess-the-verb, and throwing things on the ice, which is a real head-scratcher), for the most part they’re entertaining and fun.

Before I close, since I’ve been talking about old-fashioned puzzles, I’ll pay tribute to a moment in Zork Zero which beautifully brought together old and new styles. As one of several riddles in the game, the jester challenges the PC to “Show me an object which no one has ever seen before and which no one will ever see again!” Now, we tried lots of solutions to this — air, flame, music, etc. — but none of them worked, and none of them would have been very satisfying if they had worked. Then, at some point, we realized we had a walnut with us, and if we could open it, the meat inside would certainly qualify as nothing anyone had seen before.

Then, after much travail, we were able to find a magic immobilizing wand, then connect that wand with a lobster, which turned into a nutcracker. After that it was a matter of showing the walnut to the jester to solve the riddle. That was a satisfying moment, made up of connecting one dot to the next, to the next, to the next. But it wasn’t quite over:

>SHOW WALNUT TO JESTER

"True, no one has seen this 'ere me -- but thousands may see it in years to be!"

>EAT WALNUT

"I'm very impressed; you passed my test!

That final capper turned a good puzzle into a great one — a solution that felt smart and obvious at the same time. Unfortunately, eating that walnut wasn’t enough to defeat Zork Zero‘s hunger puzzle. (Not a hunger timer, mind you — a reasonable and contained hunger puzzle.)

For that, we needed to become a flamingo, and eat the flamingo food. RESTART!