IFDB page: Zork II

[This review contains lots of spoilers for Zork II, and some for Zork I as well. Also, I wrote an introduction to these Infocom >RESTART reviews, for those who want some context.]

Dante and I fired up Zork II right after finishing Zork I, and yep, it’s another text game from the early 1980s. There’s still no “X” for “EXAMINE”, still lots of obviously amazing things described as “nothing special”. We were more ready for that this time, which perhaps threw more light on the next layer of dissonance between that era of text adventures and the mid-’90s renaissance: the specific affordances introduced by the Inform language and libraries.

>COMPARE INFORM TO INFOCOM

Dante cut his IF teeth on Inform games, so he found interactions like this pretty annoying:

>put string in brick

You don't have the black string.

>get string

Taken.

>put string in brick

Done.

Inform would have simply handled this at the first command with the bracketed comment “[first taking the black string]”, then moved right on to “done”. (Some later Infocom games took initial steps down this road too.) Furthermore, we couldn’t refer to the resulting compound object as a bomb, even though it was clearly a bomb — granted, that’s not something Inform would have done automatically either, but it is a pretty frequent occurrence in modern text games.

Another instance Inform handles nicely but Zork II does not:

There is a wooden bucket here, 3 feet in diameter and 3 feet high.

>in

You can't go that way.

>enter

You can't go that way.

>enter bucket

You are now in the wooden bucket.

Again, Inform would have simply filled in the blank with “[the bucket]”, unless there were multiple enterable objects or map vectors in the player’s scope. And even then, it would have asked a disambiguating question rather than simply complaining, “You can’t go that way.” In fact, we could go that way.

Finally, Inform provides authors with a couple of easy facilities for avoiding “I don’t know the word [whatever]” when the player tries to reference nearby nouns. Those two magical tools are scenery objects and aliases. Thus, where Zork II gave us this:

Cobwebby Corridor

A winding corridor is filled with cobwebs. Some are broken and the dust on the floor is disturbed. The trend of the twists and turns is northeast to southwest. On the north side of one twist, high up, is a narrow crack.

>examine cobwebs

You can't see any cobwebs here!

Inform would have allowed an author to create a scenery object called “cobwebs”, and give it aliases like “webs”, “broken”, and “cobs”, so that even if she didn’t want to write a description of them, references to any of those nouns would result in a message along the lines of “You don’t need to refer to that in the course of this game.” That object could appear in multiple rooms, which I’m guessing is the flaw Zork II ran into here, since it clearly knew the word. I should also mention that it’s not just Inform that helps with extra objects, but the more relaxed memory constraints of the .z5 and .z8 formats (not to mention Glulx) compared to the .z3 that Zork II inhabits. Those early Implementors were trying to fit so many clowns into one tiny little car.

In any case, it’s worth a moment to just meditate in gratitude to Graham Nelson and his helpers for creating so many little helpful routines to smooth out the IF experience. Text adventures are forever changed, for the better, as a result of that language and its libraries. (That’s not to take anything away from TADS or Hugo, of course — I’m just thinking of how z-machine games specifically advanced.)

While the early z-machine had some pretty austere limits, some other limits were built into the Zork II experience by design. I’m thinking here of the inventory limit and the eternally damned light limit, which was even more frustrating here than in the previous game. I dunno, I suppose it’s possible that there was some technical root for the inventory limit, but it sure feels like it’s imposed in the name of some distorted sense of “realism”, a notion which flies out the window in dozens of other places throughout the game. Even if we accept the magic, the fantasy, and the allegedly underground setting (with features that feel less and less undergroundy all the time), there are just many things that make no physical sense, like easily scooping a puddle into a teapot. We can do that but we can’t carry however many objects we want to? (Again, Inform rode to the rescue here with the invention of the sack_object.)

That light limit, though. There’s no technical reason for it, and it caused us to have to restart Zork II TWICE. Not only that, it’s even crueler than its Zork I version, both because there is no permanent source of light in the game (unlike the lovely ivory torch from part 1) and because there are so many ways in which light can be randomly wasted by events beyond the player’s control. Chief among these are the Carousel Room and the wizard.

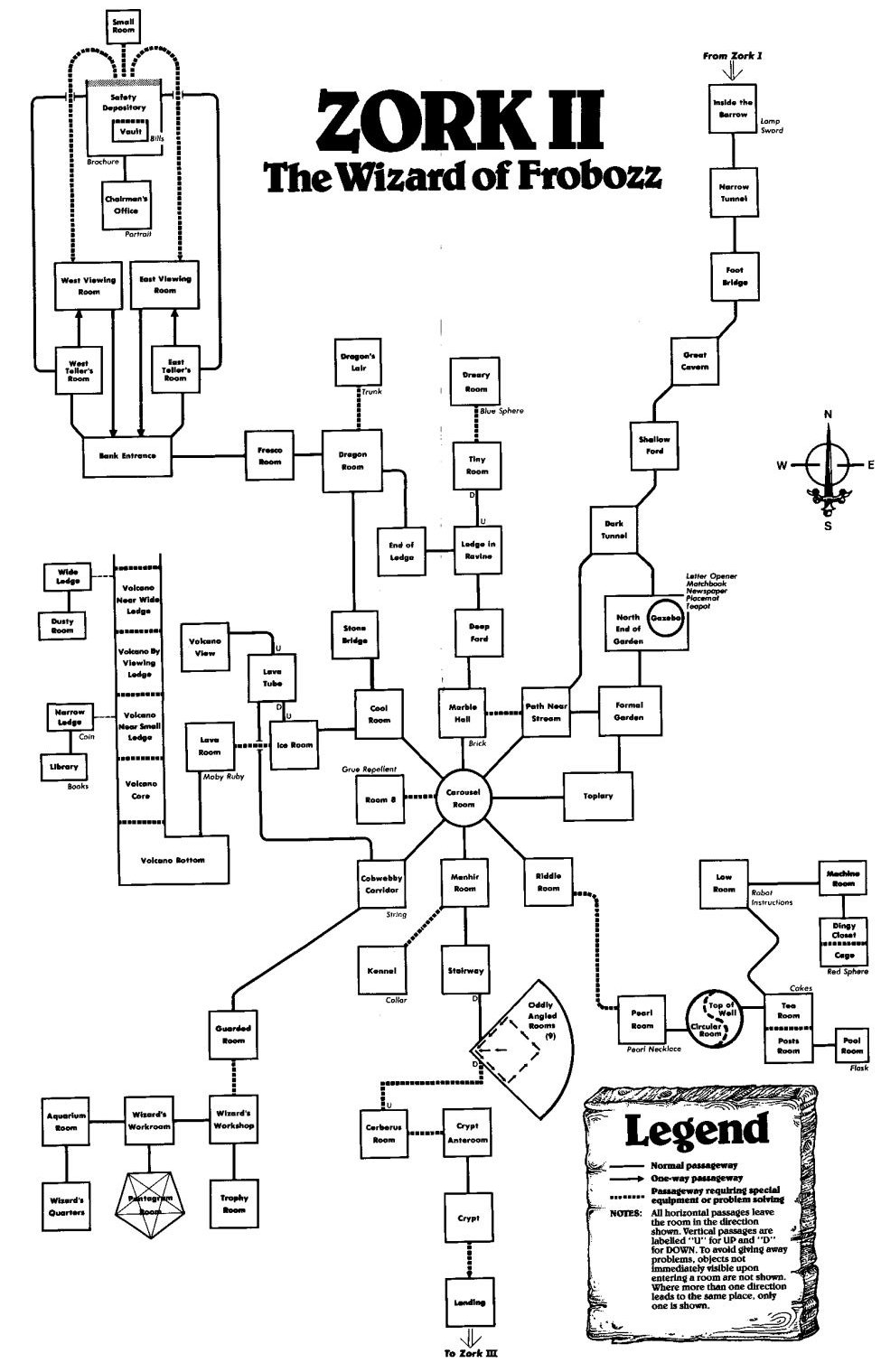

Zork I had a Round Room too, and it was entirely harmless. The Carousel Room is another story. It’s the kind of thing that sounds like a fun way to confound players, and it is, but in the case of my playthrough with Dante, we didn’t defeat it until very late in our time with the game — probably about the 75% mark of the time we spent on the game overall. That means a lot of our transcripts consist of us trying to go a direction, failing, trying again, failing, rinse, repeat, all the time ticking through that light limit, since of course all the rooms involved are dark. And it’s not as if the game makes it obvious what or where the puzzle to stop the room even is.

By itself, this direction-scrambling behavior would be quite annoying. When coupled with the fact that our light source is on an unalterable timer, it’s infuriating. Now add to that an NPC who can come along and waste your time with spells like “Float”, “Freeze”, or “Feeble”, all the time wasting yet more light, and you have one deeply frustrating game mechanic. This is that hallmark of early text games, where forced restarts were seen as adding to the “challenge.” A challenge to one’s patience, certainly. As before, Dante sat out those replay sessions.

>EXAMINE WIZARD

Since we’ve arrived at the topic, let’s talk about the Wizard of Frobozz. As has been extensively documented, Zork began life as a mainframe game, too large to fit into the microcomputers of its day, so when its implementors formed Infocom to sell it on the home PC market, they had to split up the mainframe game into pieces. That meant that the nemesis of the original game, the thief, appeared and was dispatched in the first installment of the home-version trilogy.

The thief was compelling. He could pop into your world at the most inconvenient times and create havoc, but you also couldn’t finish the game without him. With him gone in the first game, who would serve as the new adversary? Enter the Wizard. Dante was excited the first time the Wizard showed up — “It’s the title!” he said. The Wizard is a compelling character too — unpredictable like the thief but with a much larger variety of actions. He can cause a wide range of effects, but sometimes he screws up and doesn’t cause anything at all. Other times, he thinks better of meddling, and instead “peers at you from under his bushy eyebrows.”

When the wizard would show up, and the game would unexpectedly print out a stack of new text, our pulses would quicken, thinking that we’d stumbled onto something exciting. This effect reminded me to tell Dante about the days of external floppy drives — when I first played Zork II, the entire game couldn’t fit in the computer’s memory, so whenever something exciting was going to happen, the game would pause and the disk would spin up, so that the new data could be read into memory before it was displayed to the player. The excitement that accompanied that little light and whir — for instance, when leading the dragon to the glacier — was equal to any thrill I’ve subsequently gotten from a video game.

Of course, in the case of the wizard, it would turn out that nothing cool was happening. In fact it was just the opposite — we were generally about to get stymied in some amusing but nevertheless aggravating way. The wizard obviously gets more frustrating as he keeps repeating and repeating, but the variety and comedy in his spells, not to mention that sometimes he fails completely or casts something you don’t hear, really helps temper the annoyance. That said, this game is rich enough to encourage a flow state, and when the Wizard shows up to somehow block your progress, it really disrupts that flow.

Those blockages are ultimately detrimental to the game, on a level I doubt its authors were even thinking about. Parser IF is full of pauses — an indefinite amount of time can pass in between each prompt. However, the player is in control of these pauses’ length, and when we’re barreling through a game, either replaying old stuff to get somewhere or carried on the wings of inspiration, the pauses hardly feel like pauses at all. It’s more like an animated conversation. When the Wizard comes along, though, he’s a party-crasher who grinds that conversation to a halt. Suddenly we are being forced to pause, and cycle through more pauses to get through the pause.

Perhaps in some games, such a forced break would create contemplation, or an opportunity to step back and think of the bigger perspective. That wasn’t the case in Zork II, at least not for us. It just felt like our conversation had been interrupted, and we had to wait for the intruder to go away before we could continue having fun. This feels qualitatively different from the thief, whose arrival would shift the tension into another register, and whose departure may have resulted in loss of possessions, but never in paralysis that simply drained precious turns from an implacable timer.

On the other hand, the wizard has some excellent advantages over the thief. Infocom didn’t make the wizard part of the solution to a puzzle, the way the thief was, since that would have been redundant. In Zork I, the thief would foul up your plans, and had to be eliminated (though not too soon) in order to progress. Instead of this, Zork II themes its entire late game around fouling up the wizard’s plans. This conveys the sense that unlike the thief, the wizard has a separate agenda, one that isn’t centered around the player. That adds a small but significant layer of story to this game that isn’t present in its predecessor.

The way we frustrate the wizard is by getting into his lair, and doing so is one of the game’s most satisfying puzzles. The locked, guarded door to the lair starts with an arresting image: “At the south end of the room is a stained and battered (but very strong-looking) door. […] Imbedded in the door is a nasty-looking lizard head, with sharp teeth and beady eyes. The eyes move to watch you approach.” Getting past this door means disabling both the lizard and the lock, and each requires solving multiple layers of puzzles. For the lizard, it’s solving the riddle room, then finding your way to the pool, then figuring out how to drain it. For the key, it’s getting rid of the dragon, then rescuing the princess, then figuring out that the princess should be followed to the unicorn.

Then, of course, there’s the step of determining that the key and the candies are the necessary ingredients for the door. We tried many things before that! (In the process, we found one of the weirdest Infocom bugs I’ve ever seen — more about that in a moment.) And yet, even after solving it, we didn’t even have half the points! Experiences like this are what make Zork II feel so rich. Layering of puzzles, and then opening up an even bigger vista when they interlock, makes for a thrilling player experience.

Okay, so as promised, the weird bug with the lizard door:

Guarded Room

This room is cobwebby and musty, but tracks in the dust show that it has seen visitors recently. At the south end of the room is a stained and battered (but very strong-looking) door. To the north, a corridor exits.

Imbedded in the door is a nasty-looking lizard head, with sharp teeth and beady eyes. The eyes move to watch you approach.

>look through mouth

You can't look inside a blast of air.

>examine air

There's nothing special about the blast of air.

A blast of air??? What in the world is this? Dante and I never figured it out. There’s never a blast of air anywhere in the normal course of gameplay that I can find. Yet there it is in the Guarded Room, invisible but waiting to be found, apparently as a synonym for “mouth”. It gives all the usual stock responses — e.g. “I don’t think the blast of air would agree with you” as an answer to “EAT AIR”, but is simply inexplicable. Stumbling across it was one of the weirder moments I’ve ever had with an Infocom game.

There were some other amusing bugs as well:

>put hand in window

That's easy for you to say since you don't even have the pair of hands.

>roll up newspaper

You aren't an accomplished enough juggler.

>throw bills at curtain

You hit your head against the stack of zorkmid bills as you attempt this feat.

>put flask in passage

Which passage do you mean, the tunnel or the way?

We played the version of the game released in Masterpieces of Infocom — at the time that compilation was released, Zork II was 14 years old, and had sold hundreds of thousands of copies. The fact that these bugs remain is a consolation to every IF author who eventually abandons a game, its final bugs unsquashed.

>EXAMINE PUZZLES

Blast of air notwithstanding, that lizard door isn’t the only great puzzle in Zork II. The hot air balloon is another all-time winner. Figuring out the basket, receptacle, and cloth is fun, but once the balloon inflates, its ability to travel within the volcano feels magical. That balloon/volcano combo is one of the most memorable moments in the entire trilogy, and the whole section — including the bomb, the books, and the way it ties locations together — is a wonderful set piece.

The dragon puzzle is another great one. For us, it wasn’t so much a “How can we lead the dragon to the glacier” as it was a “Whoa, the dragon is following us. Where can we go?” I quite like that Zork II allows both of these routes to arrive at a solution. The placemat/key puzzle, while less flexible, is brilliant too, though it feels rooted in a time when people would have seen keyholes that a) could be looked through and b) might have keys left in them. Such a real-world experience was simply not in Dante’s frame of reference. In fact, I remember struggling with that puzzle when I was a kid, too — my dad stepped in and helped me with it, possibly aided by having lived in the kind of house where this could be a legitimate solution to an actual problem.

There are also some lovely structural choices in Zork II. The sphere collecting and placement is a great midgame — getting each one is exciting, and putting them on the stands feels appropriately climactic for the end of the second act. Similarly, the demon is a good creative variation on Zork I‘s trophy case, one who offers a marvelous sense of possibility once he’s satisfied.

We tried a variety of things with his wish-granting power, some rewarded and some not. We focused at one point on the topiary, one of the most enticing red herrings in the trilogy. We kept thinking there must be something to do with it. But “demon, destroy topiary” and “demon, disenchant bushes” got us nowhere. On the other hand, “demon, kill cerberus” was rewarded with comedy, if not progress:

“This may prove taxing, but we’ll see. Perhaps I’ll tame him for a pup instead.” The demon disappears for an instant, then reappears. He looks rather gnawed and scratched. He winces. “Too much for me. Puppy dog, indeed. You’re welcome to him. Never did like dogs anyway… Any other orders, oh beneficent one?”

Our first successful try was “demon, lift menhir”, which certainly got us where we needed to go, but much more wondrous was the notion of the demon granting us the wizard’s wand. Several times, Zork II had given us that wonderful IF experience of a broad new vista opening in response to overcoming some obstacle — the balloon and volcano is a prime example, as are the riddle and the Alice areas. When we obtained the wand, it felt like another whole range of possibility opened up. This sense eventually shrank, of course, but it didn’t fully go away either. For one thing, just the ability to “fluoresce” things and end our light source torture felt like a miracle. Of course, it screwed us up for the final puzzle, but more about that a bit later.

We also tried “demon, explain bank”, which didn’t work, but I sure wish it would have. As had many adventurers before us, we struggled mightily with the Bank of Zork. We eventually blundered around enough to get through it, but at no point did we feel a flash of insight about it, or an epiphany of understanding. I hesitate to call this an underclued puzzle. I think it’s just bad — maybe the worst puzzle in the trilogy. Dave Lebling later revealed that even other Infocommers couldn’t keep it straight.

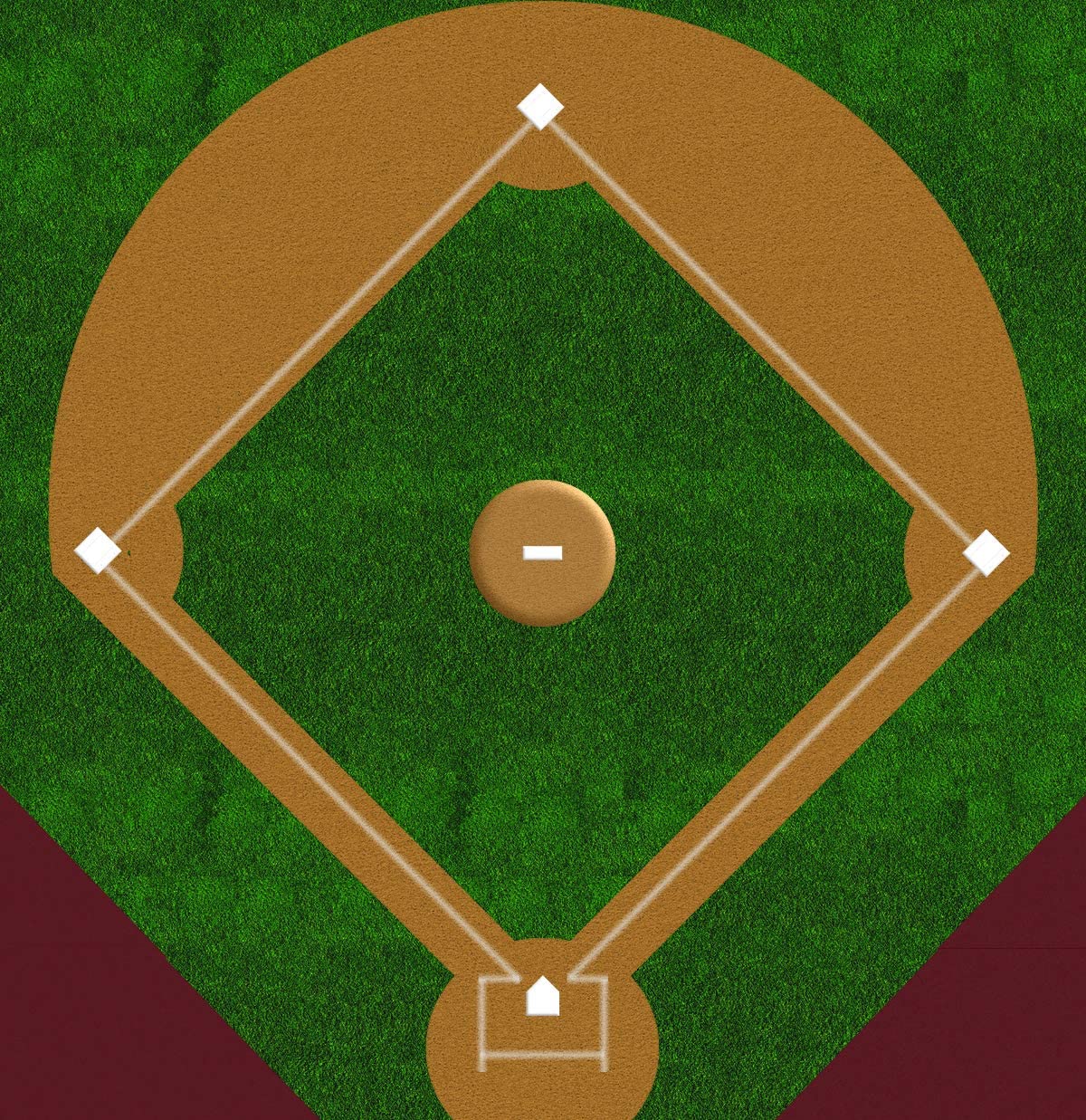

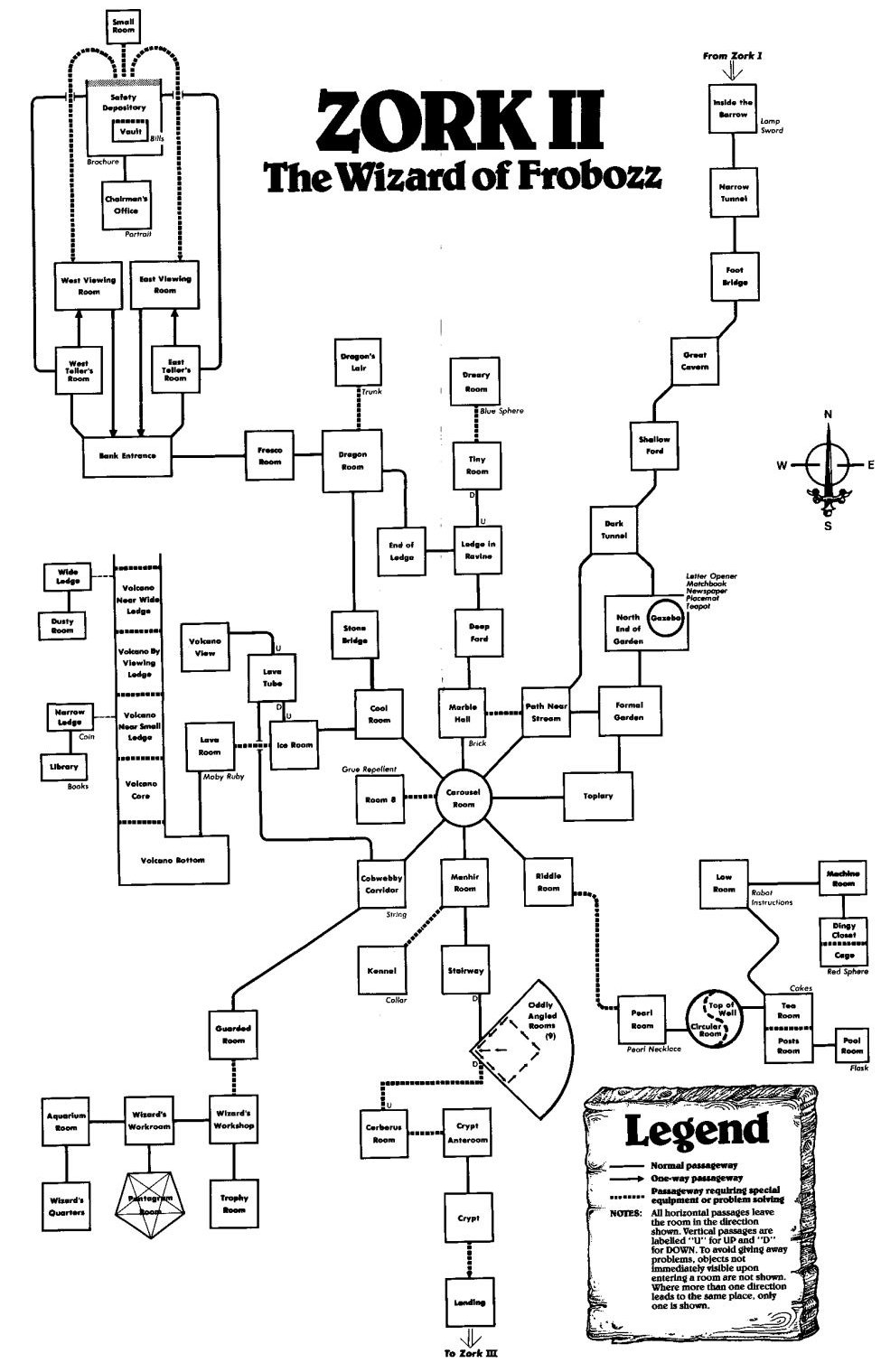

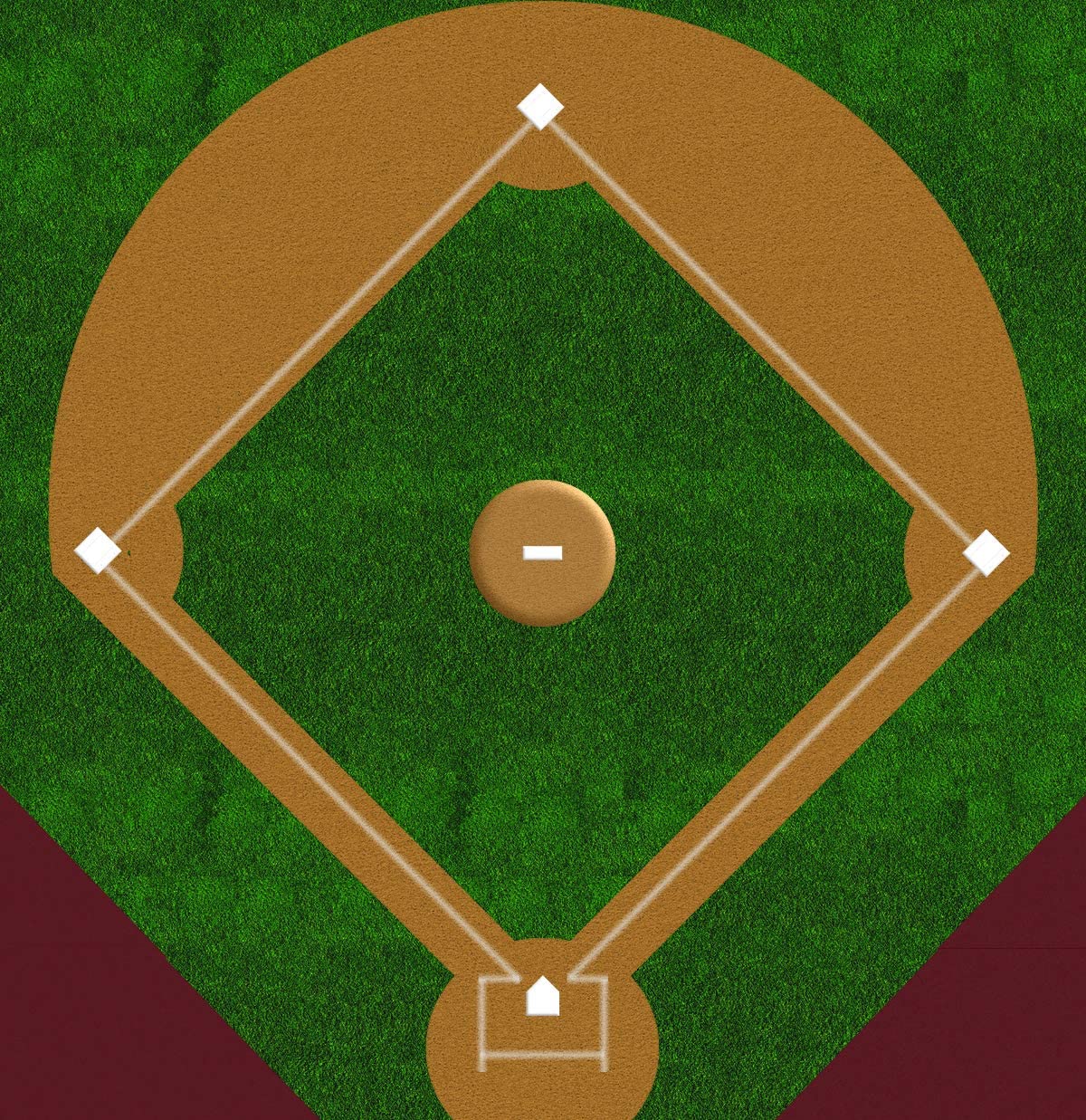

The oddly-angled rooms are another infamous Zork II puzzle, in this case infamous for requiring knowledge of baseball in a way that excluded non-Americans. I contend, though, that this isn’t even the worst part of the puzzle. Even if you do understand baseball, and even if you do make the connection between those rooms and a baseball diamond, the puzzle is still unreasonably hard to solve. Say somebody told you in advance that this is a baseball-themed puzzle, and that to solve it you’d have to traverse through the rooms like you’re running the bases. What would you do? If you’re anything like me, you’d envision the typical diagram of a baseball diamond. It looks like this — the first hit on a Google image search for “baseball diamond”:

If you conceive this diagram as an IF map, the pitcher’s mound is north of home plate, and the other bases extend in cardinal directions from the mound. So starting at home plate, to run the bases, you’d go: NE, NW, SW, SE. Right?

Well Zork II, for reasons I don’t understand, tips the diamond on its side. To run the oddly-angled bases, you have to pretend that home plate is west of the pitcher’s mound, and therefore travel SE, NE, NW, SW. That reorientation delineates the difference between “Oh, ha, it’s a baseball diamond!” and “How in the hell is this a baseball diamond?” So take heart non-Americans (and Americans who don’t know the first thing about baseball) — that “inside baseball” knowledge isn’t nearly as helpful as you might think.

The other puzzle that really stymied us was the riddle. For those who haven’t played in a while, the riddle is this:

What is tall as a house,

round as a cup,

and all the king’s horses

can’t draw it up?

This was an interesting one for me to observe. I remember solving it quite readily when I played Zork II as a kid. For whatever reason, the words just clicked for me. Dante, on the other hand, really grappled with it. He took about thirty different guesses over the course of our playthrough before I started feeding him hints. The guesses fell into a few different categories:

-

- Contrived answers: a gigantic egg, an osmium sphere (because osmium is so dense)

- Jokey reference answers: the Boston Mapparium (an enclosing stained-glass map globe that he learned about from Ken Jennings), an enemy city support pylon (referencing The City We Became by his fave author N.K. Jemisin), a geode (from the same author’s Broken Earth trilogy)

- Logical guesses, albeit not very Zorky ones: power pole, pipe, subway

- References to this game or the previous one: rainbow, tree, menhir, dragon, xyzzy, the letter F, barrow, glacier, carousel, lava tube, gazebo, cerberus, balloon, hot air balloon, cave, carousel room, mine, coal mine

- Just off-the-wall pitches: hill fort (a Celtic thing inspired by “barrow”), tentacle, squid, octopus

Finally I started hinting around pretty heavily to think about holes in the ground, but even then he said “hole”, “bore hole”, and “quarry” before he got to “oil well”, which wasn’t even the game’s intended answer but which still provoked the success response because it contained the word “well”.

Riddles have a big risk/reward proposition as an IF puzzle. If you solve one, you feel so chuffed and clever. But if you don’t solve it, you may just be stuck, especially in the absence of any other hinting mechanism. Perhaps in the days where players were willing to sit with stuckness for extended periods of time, the calculus was a little different, but now puzzles like this flirt with ragequit responses, which I would argue has turned into a failure on the game’s part.

The final puzzle of Zork II felt like a mixed bag to us. It’s intriguingly different from Zork I, which basically led you to the ending after you’d deposited all the treasures. In Zork II, you can get all the points but not be finished. Indeed, the response to “SCORE” at this point is:

Your score would be 400 (total of 400 points), in 753 moves.

This score gives you the rank of Master Adventurer, but somehow you don’t feel done.

There’s one more puzzle to solve, and for us it was difficult enough to require a hint, something we’d managed to avoid for the rest of the game. Nevertheless, we ended up satisfied, feeling that it was tough but fair — essentially it requires being lightless, something that willingly surrenders in the battle we’d been fighting the whole game. We completely missed the hint — a fairly obscure phrasing on a can of grue repellent — and therefore floundered.

For us, the barrier to solving this puzzle was the flip side of the sense of possibility that the wand allows. For example, the ability to make things fluoresce with the wand so fascinated (and relieved) us that we never walked in there without light. Our continued frustration with light limits also made this behavior very enticing. On top of that, it seemed like no coincidence that “Feel Free” was a double-F, like a more powerful version of the wizard’s spells. Oh the number of places where we pointed the wand and incanted “Feel Free”, to no avail. On the other hand, having solved this puzzle with hints prepped us to solve on our own a very similar puzzle in Enchanter, but that’s a topic for another post.

I think I’ve spent more time in this post criticizing Zork II than I have singing its praises, so it may be surprising when I say that this is my favorite game of the trilogy. I have plenty of affection for parts 1 and 3, but to me this is where the best parts of Zork fully jelled. The humor works wonderfully, the imagery is fantastic, and the structure mixes richness and broadness in a way that makes for wonderful memories of gaming excitement. And sure, its bad puzzles are bad, but its good puzzles are great — deeply satisfying and marvelously layered. Zork I established the premise, and Zork III deconstructed it, but Zork II fulfilled it, and in the process provided me with many happy hours that I loved revisiting with Dante and his fresh eyes.